"It’s just a Ponzi scheme"

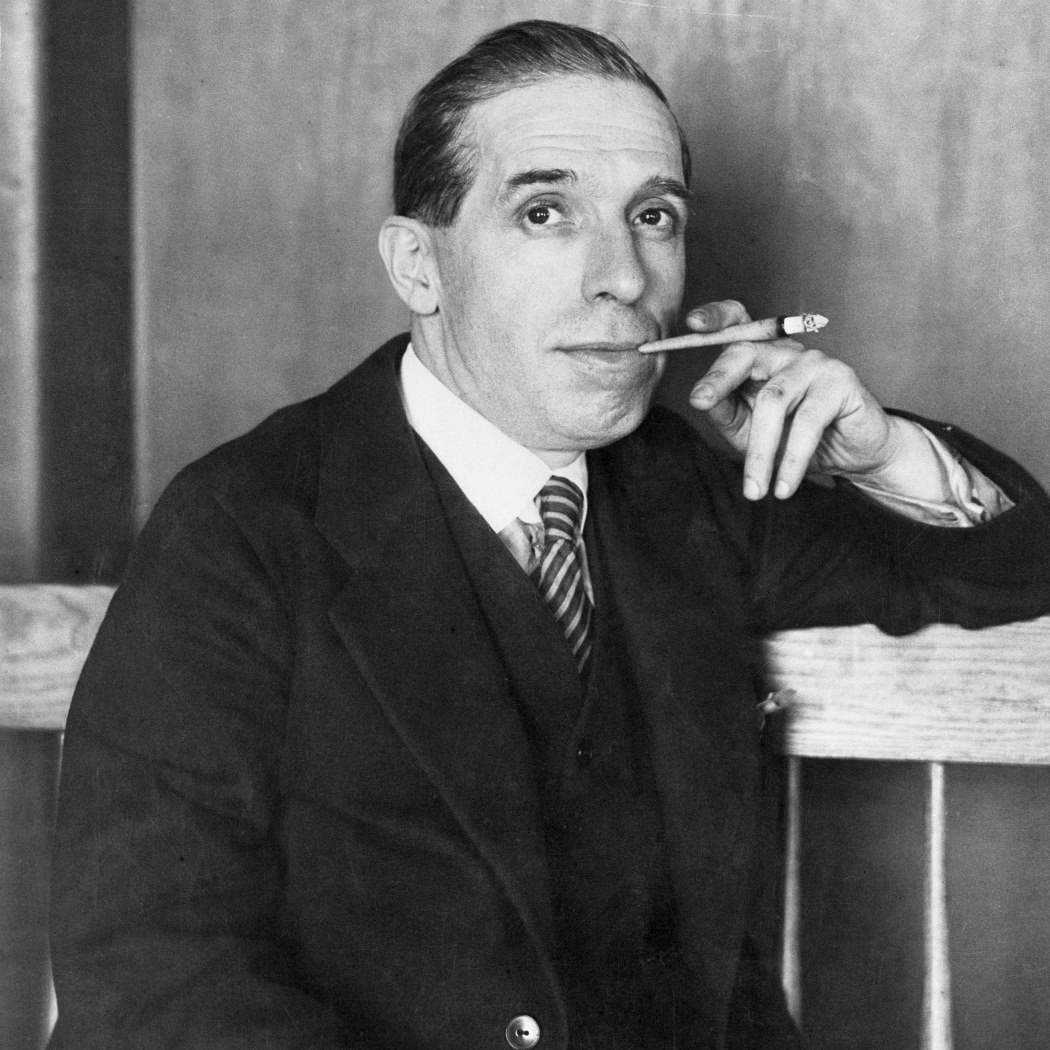

You’ve heard that line — whenever a shiny new investment collapses or a crypto founder disappears with millions. It’s the universal label for financial deceit. But few ever ask: Who was Ponzi? And how did his name become the symbol of greed itself?

Charles Ponzi wasn’t born rich or powerful. He was an Italian immigrant, broke but brimming with ambition — a man desperate to beat the system. What he built in 1920s Boston wasn’t just fraud. It was a masterclass in psychology and timing — the first viral illusion of wealth. He promised investors 50% returns in 45 days,people believed him. Banks backed him. Newspapers called him a genius.Until, of course, the math caught up.

America’s Roaring 20s

Post–World War I America was booming. Factories thrived, cities glowed, and a new faith had taken hold — the belief in easy money. Immigrants chasing the American Dream poured through Ellis Island( Does it remind you of Vito Corleone from Godfather 2). Among them was Charles Ponzi, who drifted from job to job — waiter, clerk, even forger — always searching for a clever shortcut to fortune.

Then one day, flipping through his mail, Ponzi stumbled upon something ordinary yet revolutionary: the international postal reply coupon (IRC). To most, it was just bureaucratic clutter. To Ponzi, it was arbitrage gold. Buy coupons cheaply in Europe, redeem them in America for higher-value stamps, pocket the difference — in principle, legal and brilliant. In practice, impossible.

The Scam

Ponzi set up a small office on 27 School Street, Boston in 1919 and began promising friends and contacts huge profits. He claimed the IRCs could deliver returns exceeding 400%, and early investors received real payouts — paid from the money of new investors. The buzz exploded. By January 1920, he had founded the Securities Exchange Company, paying 18 initial investors promptly and attracting thousands more. Within months, investments skyrocketed:

February–March 1920: $5,000

June 1920: $2.5M (According to WSJ)

By July, Ponzi was handling millions per day. Ponzi even bought controlling interest in Hanover Trust Bank, hoping to consolidate his empire. Investors poured in from all walks of life — working-class immigrants, Boston elites, even police officers. Most reinvested rather than cashing out, feeding the illusion further. Nearly 75% of Boston’s police force had invested at some point.

Ponzi lived extravagantly: mansions, luxury cars, first-class travel, and even businesses like a macaroni and wine company — all to maintain appearances and placate investors. Yet behind the facade, the scheme was mathematically doomed. For every $1,800 invested initially, he would have needed 53,000 postal coupons to actually realize the profits. For all 15,000 investors, it would have required Titanic-sized shipments of coupons from Europe. He wasn’t trading — he was paying Peter with Paul means giving new money to the old investors.

The Downfall

Ponzi’s rise drew suspicion. Investigative reporters at The Boston Post and Massachusetts authorities began digging. By July 1920, audits revealed Ponzi’s company was deeply insolvent. The Post ran front-page exposes, uncovering prior criminal activity and the impossibility of the IRC profits.

Panicked investors rushed to withdraw funds. Ponzi scrambled, paying millions in one day, but the house of cards collapsed. Banks failed. Massachusetts authorities intervened. By August, Ponzi was arrested and charged with mail fraud. Bail attempts failed, and his empire crumbled. Investors lost approximately 20 million (roughly $314 million today), wiping out life savings, mortgages, and small fortunes.

Even before his trial, Ponzi’s name had entered the language. Advertisements warned: “Don’t be Ponzied.”

The Timeless Lesson

Charles Ponzi didn’t invent greed; he exposed it. His scam worked because it preyed on something eternal — the human craving for effortless wealth and the belief that this time, it’s different. A century later, his blueprint still lives on — in crypto collapses, fake investment apps, and get-rich-quick schemes dressed in modern code.

So the next time someone promises “guaranteed returns”, remember the man who made that promise first — and how it ended. Because in finance, and in life, there’s no such thing as free profit.